PNLT ORIGIN STORY

The Parkdale Neighbourhood Land Trust (PNLT) was created as a response to gentrification, by local residents and agencies seeking to protect the social, cultural and economic diversity of Parkdale in a period of significant change.

A CLT TO PROTECT COMMUNITY SPACE

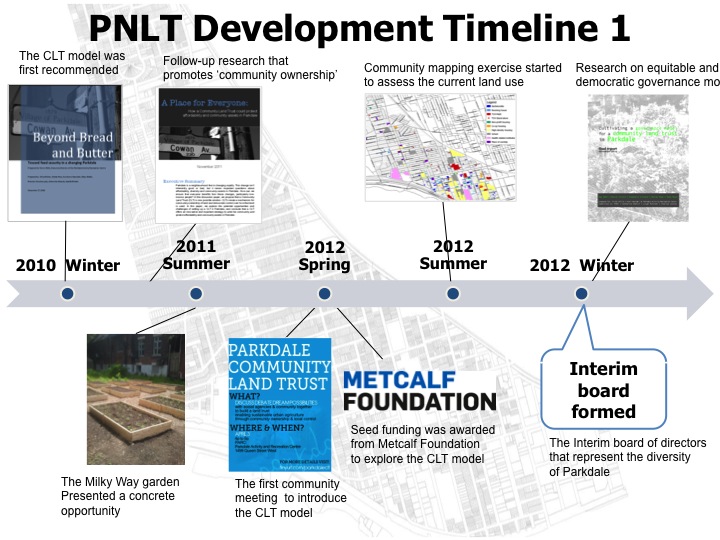

In 2010 the Parkdale Activity and Recreation Centre (PARC), a local multi-serve Agency with 37–years of experience in anti-poverty work, commissioned Professor Katherine Rankin’s University of Toronto Planning Class to study the impact of commercial gentrification on local food security. The study this class produced, “Beyond Bread and Butter,” highlighted 10 directions for community action, including the development of a Community Land Trust (CLT). As the report makes clear:

A challenge posed by gentrification is the pressures from… market-driven real estate developments. Through gentrification, small businesses serving lower income groups are being gradually displaced in favour of shops catering to more affluent consumers. The loss of such services and commercial spaces results not only in declining affordability and accessibility of food options but also in losing community spaces where people feel comfortable…

A challenge posed by gentrification is the pressures from… market-driven real estate developments. Through gentrification, small businesses serving lower income groups are being gradually displaced in favour of shops catering to more affluent consumers. The loss of such services and commercial spaces results not only in declining affordability and accessibility of food options but also in losing community spaces where people feel comfortable…

Community land trusts (CLT) can provide alternative land ownership and management to protect community space and its affordability. CLT functions as a mechanism to remove land from the speculative real estate market and gentrification pressures (Bunce, personal communication, 2010). Instead, the land is held in perpetuity by CLT for the community purpose. Thus, unlike short-term government programs and/or subsidies, CLT is able to secure long-term affordability and community control over space.

A MEANS FOR GREATER COMMUNITY CONTROL OVER DEVELOPMENT

At this early stage, the idea of building a CLT in Parkdale was viewed as a long-term project, unlikely to be completed in the short or even the medium term. In a second report, “A Place for Everyone“, written during this same period, Brendon Goodmurphy and Kuni Kamizaki justified the need for a CLT in Parkdale, arguing that the protection of “affordability and community assets requires the entire community. It is an issue that affects everyone because it is ultimately about land – who has access to it, how itʼs developed, and who benefits from it. A community land trust… could give Parkdale greater control over development and managing change.”

The authors went on to set out a series of short, medium and long-term goals:

The authors went on to set out a series of short, medium and long-term goals:

- Short term: Continue to garner community support, and broader support across Toronto, building a membership base and answering questions/concerns

- Medium term: Conduct a detailed Feasibility Study and create a Business Plan for the Parkdale CLT, including a budget for the first three years, and a fundraising strategy.

- Longer term: Incorporate the Parkdale CLT as a non-profit organization, apply for charitable status, and finally run elections for the first official Board of Directors (who will then take over as the governing body).

In 2012, PARC received a grant from the Metcalf Foundation to engage local residents and organizations about the idea of creating a CLT in Parkdale. The public meetings were well attended, proving broad interest and support.

PNLT ESTABLISHED AS AN ORGANIZATION OF ORGANIZATIONS

In 2014, The Neighbourhood Land Trust was officially incorporated as a non-profit organization. The organization was known in the community as the Parkdale Neighbourhood Land Trust (PNLT).

PNLT’s first Board formed as “an organization of organizations”, consisting of representatives from seven groups including PARC, Parkdale Community Legal Services, Greenest City, Sistering, West Neighbourhood House, the Roncesvalles and Macdonnell Residents Association and Parkdale BIA. In these early days, the board met in PARC’s boardroom (with food provided by local social enterprise Raging Spoon) to discuss how to best develop a democratically-run CLT that might one day own and preserve community assets.

This provisional Board established an exciting new platform for discussions about land use and community assets. Under the leadership of Chair Judy Josefowicz, it took on the practical work of developing backbone organizational structures, policies and PNLT’s first three Year Strategic Plan. Five volunteer working committees were established, and 180 residents were recruited from the neighbourhood to establish an initial membership base.

On October 27th 2015, the PNLT held its first official Annual General Meeting, at which point control was handed over to a community-elected Board.

INCORPORATION

Incorporation is a legal process that can be outlined in several steps. You can incorporate your organization by firstly creating a name for it. Secondly, your organization will be required to complete a series of government forms for it to become incorporated as a not-for-profit corporation. In Canada, these forms are Form 4001 – Articles of Incorporation and Form 4002 – Initial Registered Office Address and First Board of Directors. The information that you include in these forms is required by the Not-for-profit Corporations Act (NFP). These forms vary from country to county, however, it will be useful to know key information such as:

-

- The corporate name of your organization (and previous names, if applicable)

-

- The minimum and maximum number of directors

-

- Organizational purpose

-

- Restrictions on activities

-

- Organization structure of members and their voting rights

- Property that will remain upon liquidation

To understand these articles more in-depth, please click here.

If you are considering becoming a registered charity, you should visit Charities and giving (Canada Revenue Agency) to assist you with completing your incorporation documents. This is to ensure that you will be meeting the requirements to obtain charitable status.

Non-profit or Charity?

Although non-profit organizations and charities operate on a non-profit basis, they are each different in some ways. During the process of developing your corporate By-Laws and objects, decide whether you want your organization to be a registered charity or a non-profit. A not-for-profit has more fluidity as it pertains to political activity, fundraising, and user fees, but they are unable to issue tax receipts. A registered charity, on the other hand, are regulated by the Canada Revenue Agency thus making it permissible for them to provide tax receipts to their donors. Keep in mind that with charitable designation comes more restrictions.

Incorporating a Non-profit

Registered charities, as defined by the Government of Canada, are created and situated in Canada and are designated as charitable organizations, public or private foundations. A key stipulation of registered charities are they must exclusively be initialized and operated as registered charities, and their resources have to be used to carry out charitable activities and have charitable purposes.

A registered charity has a series of regulatory obligations that it must adhere to sanctioned by the different levels of the Canadian government (federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal). Further, a registered charity must be accountable to those involved in its charitable activities, to its volunteers, to its donors, and to the members of the public.

Incorporation of a charity allows for more control over assets. For example, if your organization was to acquire real property, with incorporated charitable status, you will be able to hold title to that property, rather than it being held in trust by a trustee.

To register your organization as a charity for income tax purposes under the Income Tax Act, you will be required to fill out the form T2050 Application to Register a Charity Under the Income Tax Act. On this form, you will be asked questions about the organizational structure, the activities of your organization, the charitable purposes and so on. Be sure to make any necessary revisions to your organization’s Objects and Bylaws of incorporation so that you meet Revenue Canada requirements.

Once your application is approved, your organization will receive a notification of registration letter containing your organization’s rights and obligations, as well as its charitable business number.

Corporate By-laws

Creating By-laws are a necessary component of incorporating your organization under the Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Act. By-laws are the regulatory tools that govern what your organization and its members and users can and can not do. By-laws can be changed when necessary to meet different organizational needs.

The NPA provides a standard list of provisions to be included in your corporate by-laws, or you can use Corporations Canada Bylaw builder.

Defining membership categories and figuring out how to organize your board is crucial to finalizing your by-laws. It will also be beneficial if you can retain the membership of a lawyer on your governance committee so that they can ensure that your by-laws align with the applicable government regulations.

A fair amount of the by-laws that we created for PNLT were standard to most non-profits, though the sections about members and how the board works – the parts unique to PNLT and CLTs more generally – took more discussion by the committee.

Membership Types

Concerning the membership categories, we reflected a lot on how the three-part CLT board model should be adapted to specifics of PNLT. We came up with “core,” “community,” “organizational,” and “supporter” categories which contained a mixture of local stakeholders and neighbourhood residents. These categories were created after a great deal of discussion about details such as how each would be nominated, whether it was sufficient to work in Parkdale or if residency was needed, whether to charge a membership fee, etcetera. These questions will probably result in different answers for your organization, as has been the case with other CLTs. Moreover, once we were able to define membership categories and figure out how to organize our board to ensure that these groups were inclusive and representative of the community being served, the rest was pretty straightforward.

CLTs are democratically-controlled by their membership. Membership is generally open to all residents of the community. More specifically, representatives from various interested community groups, such as local business and non-profit housing organizations.

An elected board of directors oversees the activities of the organization. This board is elected by the membership and is normally structured to balance the representation from the various interest groups.

CLTs are typically run by small staffs, and many rely entirely on volunteers. The staffs are responsible for fundraising, property management, and the development and acquisition of land for the benefit of the community.[/x_accordion_item]

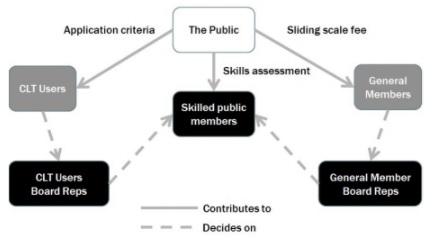

Establish a governance model appropriate to your community

UN-Habitat observes that most CLT governance models are community-based, user-controlled, and its structure consists of three parts. Governance of the CLT should be community-based in that people who use the lands or reside in surrounding areas should guide its development, while user control implies that users of the CLT, not absentee investors, for example, should control its operations. The figure below displays the governance structure of our community land trust.

In order for us to develop the community-based governance model we reviewed the literature on governance and public participation, conducted a review of different CLTs in North America, supplemented by interviews with United States-based CLT practitioners. We additionally, conducted key informant interviews with community members in Parkdale to inform our recommendations for a governance model for our land trust.

We prioritized the following four qualities when creating our community-based governance model for our neighbourhood:

a) Equitability

The CLT requires a governance model that fairly represents and balances diverse and unequal interests. Equity will be ensured when it is clear that the board is composed of members who can serve these different interests while simultaneously pursuing the common goals of the CLT. Consensus decision-making will contribute to equitable governance, as will specific policy frameworks intended to foster inclusive spaces through which the board, in collaboration with membership, can achieve its goals.

b) Efficacy

Your CLT must ensure that it operates effectively to accomplish its goals as effective governance is the backbone of a successful organization. Your CLT may face challenges in attempting to ensure representation if it is operating in a diverse community while at the same time making sure the board reflects the necessary skills and experience for effective governance and operations. This can be achieved through training and capacity building at the board level or recruitment of board members with specific necessary skills. It can also involve partnerships with organizations that can offer their skills and experience to your CLT, or seeking out support and resources from political officials or existing CLT networks.

c) Sustainability

Continued outreach is key to maintaining and growing membership while advancing community development goals. Second, implementing measures to ensure the model can adapt if necessary is paramount, for both the neighbourhood and the project are likely to change over the years.

d) Practical Feasibility

The most important concern and challenge for existing CLTs in other jurisdictions, regardless of size or governance model, is funding. First Homes properties explained the need for financial sustainability “you are making a long-term commitment to people’s lives, so you also have to make a long-term commitment to the organization – and to organizational sustainability. Striking a balance between sources of revenue and sustainability is necessary for effective stewardship”.

For more information on how we developed our community-based governance model, click here.

Set up a Board of Directors

The board’s main responsibility is to represent the membership in making decisions for the CLT. The board should be representative of the community involved in and impacted by the CLT, which depends on adequate outreach to as many people as possible. Board members are volunteers and must be voted in by members of the CLT as outlined above.

The board of directors will follow the tripartite membership that is typical of classic CLTs. The number of board members will fall within a range of 9-18, and be split into three equal groups. The first group will consist of CLT users, the second group will consist of general members, and the third group will consist of public members. Within the board, various members must take on additional duties that serve a function for the management of the board. For example, the board will require a chair, vice chair, treasurer, and secretary. Other skills that are required by the board may include financial management, fundraising, legal, monitoring and evaluation, networking, policy-making, and planning. In order to establish what skills exist on the board, a skills assessment should be performed when a new board is elected. The skills that are not accounted for will be added to the board with the public members.

Recruiting Board members

Prior to the incorporation of PNLT as a non-profit organization, there was a great deal of community organizing taking place. The community involved consisted of pre-existing engaged residents and local organizations.

In regards to the recruitment of board members, members of the land trust were more focused on those who had previous land trust and non-profit organization experience as well as knowledge of governance and legal related matters. Initially, recruitment was more centred on connection and skill and as time progressed, the direction shifted to looking for community members that possessed individual passion. It is integral that the composition of the Board of Directors represents a balance of technical skills and representation to enable the Board of Directors to make informed, well-balanced decisions on the economic viability and social impact of its activities.

Once the board was developed, they were heavily involved which was integral to the operation of the land trust, which resulted in less focus on governance. Although staffing does play a large role in sustaining the organization, in the preliminary stages of a non-profit, community involvement is necessary.

Hosting Annual General Meetings (AGM) contributed to a seamless recruitment process. Consequently, it was noted that there needed to be more opportunities for training particularly for those who had no previous board experience. Facilitating training would contribute to more community representation on the board, which is recommended to capture a wide range of local resident perspectives.